Inflation Is Getting Worse, Not Better

A look ahead at the inflationary future

I lived through the inflation of the 1970s, and I remember some things. I was just a kid, but I got interested in economics in high school because of inflation, interest, and recessions that seemed normal to me but terrifying to people my parents’ age.

So, I thought I’d tell you about what’s about to happen in America.

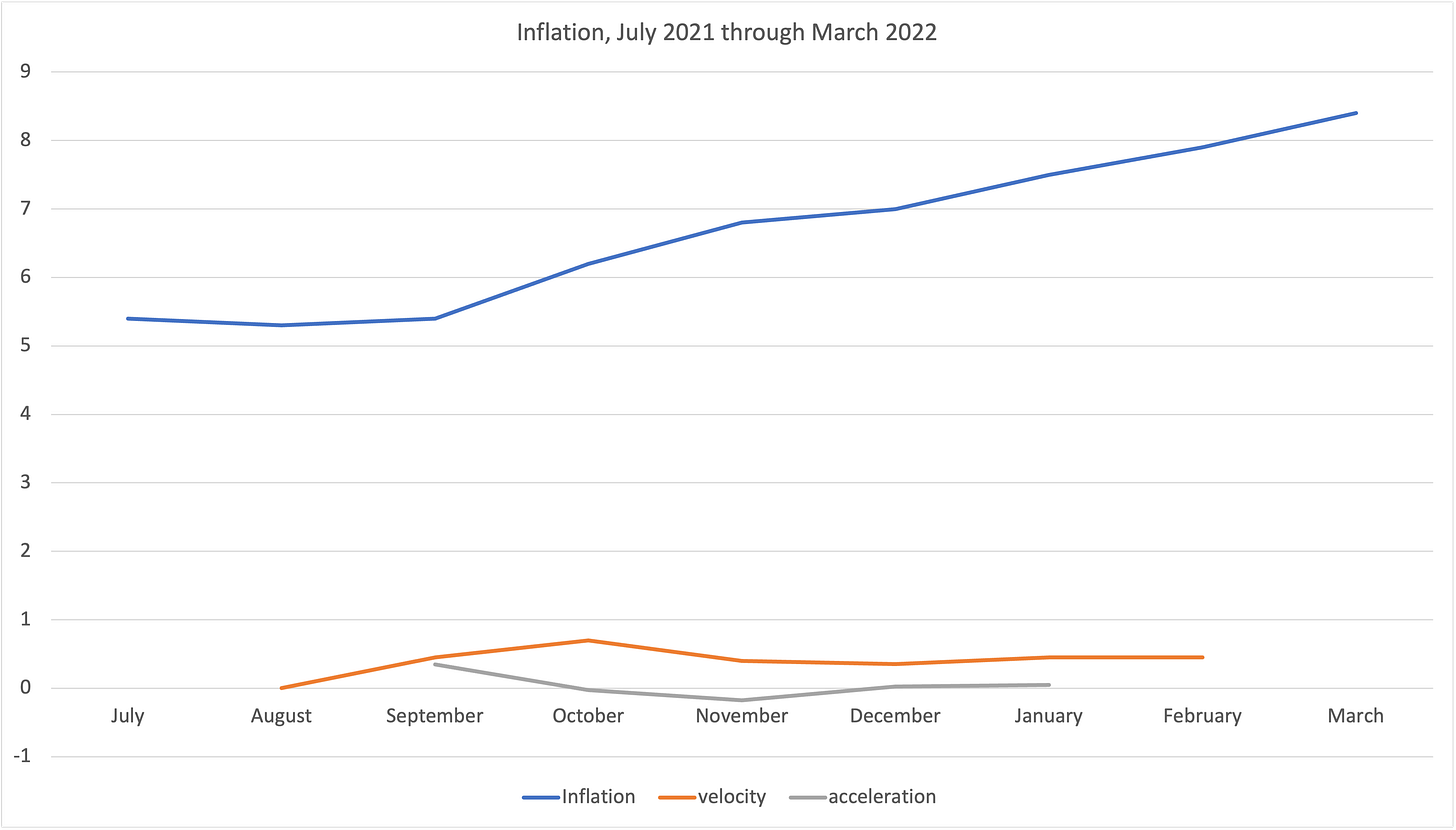

This chart shows monthly inflation rates since July 2021, along with velocity and acceleration. The blue line is inflation.

Acceleration, the gray line, is the change in velocity over time. And acceleration can tell you what’s likely to happen in the near future. But the orange line, velocity, is a bit easier to read.

In this case, velocity is holding pretty steady about .5 per month and acceleration (though January) is also flat. That means we can expect monthly inflation to increase at about a half a percentage point a month, which is pretty consistent for recent months. Just look at the month-over-month change in this table, especially the last four months:

Consumers expect prices to increase about half a percentage point per month. A lot could change in a hurry, but we’re seeing buying behavior consistent with this expectation, which means prices will continue to rise. People are willing to pay that increase. For now.

If this is the case, September’s inflation number, which will be the last before November’s election, will about 11.4% annual inflation. That should be very good for candidates who are not incumbents, but it also points out the problem with inflation: it feeds on expectations.

Inflation Accelerates Spending on Inferior Goods

Let’s say I have $100 to spend on anything I want. It’s extra money. Normally, I would buy something small right away, then hold onto the rest until something came along that I really wanted. But what happens if I expect prices to increase?

Well, that $100 starts burning a hole in my pocket. Here's an example from real life.

My weightlifting coach told me I should invest in a pair of squat shoes about a month ago. So I started researching squat shoes, or weightlifting shoes as the marketers call them. I found out they are expensive. Cheap ones I looked at were about $79.50, and the ones recommended to me were $159.

I thought I’d wait to see if they went on sale. Then, last Saturday, I looked again. The cheap ones were now $89.50 and the good ones $169. So I immediately bought the cheap ones, which I’ll probably regret.

And there went the $100 fun money.

If the price of the shoes had remained the same, I might have bought the better pair at $145. But prices are rising fast, so I bought the less desirable pair for $90. This told the market something important: you can raise prices on less desirable products, and people will still buy them.

This makes no sense, but it’s true. People will shift their spending to lower quality (or lower perceived quality) items until the price of the lower quality items becomes close to the price of higher quality items.

You’ll see this with beef. Right now, people are paying more for inferior steaks. But the price of ribeye is rising slower than the price of chuck steak. At some point, people will opt for the ribeye over the chuck steak.

This happened in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Throughout the last-half of the 70s, generic, no-name, and store brand stuff increased in popularity. My mom hated generic anything, but by about 1978, she had no choice but to “indulge” in generic snacks and beverages.

Back to those squat shoes for a moment. Both pairs increased in price by $10 in four weeks. That was a 6% increase for the expensive pair, but a 16% increase for the cheapos. At those rates of increase, the inferior shoes would soon be over $100, but the good pair would still be under $200. At that point, according to pricing psychology, I probably would have bought the good pair at $192 over the cheap pair at $106.

(Yes, our brains really work that way. We categorized prices based on the first digit, the number of digits, etc. before we consider the difference in price. So our brains tell us anything between 100 and 199 is in the 100 category—more or less the same price.)

But, let’s keep moving.

Sometime in 1980, the generics had increased in price to match what the name-brands cost in about 1978. At that point, Mom said “to hell with it” and went back to Bounty paper towels, Reynolds aluminum foil, RoldGold pretzels, and whatever name-brand potato chips were big then.

Inflation hadn’t stopped—people like my mom just gave up trying to fight it. They adjusted the thermometer and bought what they wanted.

And that surrender cause inflation to really took off. Inflation in January 1980 was 13.9%. Psychology was taking over.

Inflation usually starts as a function of supply and demand. When there’s more demand than supply, prices go up. But, at some point, inflation goes up because people expect prices to rise. It doesn’t matter at that point how much stuff is available on the market—everyone charges more because everyone’s paying more.

And, right now it’s easier to increases prices because people are fueling inflation with credit cards. Via Washington Times:

A new report by the Federal Reserve Thursday shows that consumer credit, the amount advanced to individuals for purchases, spiked by $41.8 billion across the U.S. in February. The rise is significantly higher than the $8.9 billion increase in January.

Did you get that? In January, consumer increased their debt by $8.9 billion. In February, they increased debt by $42 billion. That’s a 5x increase in one month.

And prices only increased faster in the month of March! The March increase in consumer debt could reach $200 billion.

Now, what happens when consumer use debt to fight inflation?

No one really knows.

It’s been 40 years since the US experienced inflation approaching double digits, but credit cards were not a common vehicle of exchange in 1980. Everybody had credit cards, but they used them for special purchases. People talked about people who used credit cards at the supermarket, and not in a good way. In 1980, buying groceries on credit (except for American Express) was tantamount to bankruptcy.

So, we don’t really have a historical benchmark for what happens when people fight inflation with debt since credit cards weren’t as ubiquitous the last time we experience this kind of inflation.

But we can guess.

At some point, the credit card companies will lower credit limits. Not just on the people with rapidly-increasing balances, but across the board. Then, people will have to pay inflated prices with cash—cash that would otherwise have paid their next credit card bill. Or their rent or mortgage. Based on my experience, these consumers will shift buying from online with plastic (debit or credit) to in-store with cash. The reason is simple: autopay.

Most people pay most of their bills with autopay. As their bills increase quickly, and without room on their credit cards for daily necessities, they’ll soon need to withdraw a lot of cash on payday, before the autopays wipe them out. They’ll use cash to buy necessities and deal with the bill collectors later.

This means a lot of delivery services will start hurting. Gig workers who now make a living carrying $7.00 worth of Taco Bell to consumers for a $15.00 delivery fee will have no deliveries to make. Uber and Lyft will either need to take cash or watch their old fares hop into cabs that do. Oh, and with rampant crime spikes in major cities, all those people carrying cash will become very attractive prey.

You see where this is going?

A recession is coming. Either the Fed will force one by jacking up interest rates to 1980s levels, or people will run out of money with which to buy things. Bill won’t get paid. Houses will get foreclosed on.

So pick your reference year: 1981 or 2008. It’s going to be one of those.

Unless, of course, Uncle Joe Biden pulls a miracle out of his . . . his . . . oh, you know, the thing!

Online spending PLUNGED in March as consumers put gasoline and food on credit cards, as predicted. https://www.zerohedge.com/personal-finance/us-retail-sales-growth-slowest-13-months-online-spending-plunged

Your observation about generic/private label products was absolutely correct. In the late 70’s Kroger went all in on the yellow label “Cost Cutter” brand….it was everywhere in their product assortment. When consumers decided they wanted national brands (i.e. Cheerio’s, Oreo’s etc.) Kroger was so heavily invested in private label and no exit strategy they almost went bankrupt.