The Trouble With Truth

You won't win any arguments with this, but it will help dismiss error and speculation--and, perhaps, pity those who think their truth is truth

Truth is difficult to comprehend, as demonstrated by Pontius Pilate. “Qui est veritas?” he asked Christ. “What is truth?”

What makes truth difficult for us is that we let our malformed intellects get in the way of simplicity. Human ideas of fairness, equity, and the like cloud our vision of the truth. To overcome these deficits, though, we must use the deficits. We must apply reason to the question “what is truth?”

Truth has two characteristics whose contemplation satisfies the intellect by giving it something to chew on. Those two characteristics are:

Truth must be completely true and contain no error.

Truth is immortal—what is true to today was always true and will always be true.

These two characteristics work together to both narrow and broaden truth.

Because truth must be pure truth—whole and exclusive of error or speculation—much of what man calls “truth” must be rejected. We believe we speak the truth when, upon looking out the window and seeing a driving rain, we say, “it is raining.” But anyone who has taken a freshman level philosophy class knows, such an assertion will be immediately challenged. “Is it raining on the Serengeti?”

So we narrow our focus. “It is raining here,” we say.

“I’m not wet. You’re not wet. It must not be raining here.”

“Well, it’s raining outside here,” we clarify.

“Is it raining underneath your car in the parking lot?”

You know the drill.

While maddening to the freshman, the exercise teaches us that truth is a narrow thing. To be true, a statement be precise and accurate. The scope of truth must become tiny to exclude all error and speculation. Very narrow.

This demand for precision and accuracy is why most people take but one philosophy class, by the way. Precision and accuracy hurt the brain.

Yet, truth is remarkably expansive—more expansive than anything conceived by man. For truth always was and always must be. Nothing can be true one moment and false the next. What was true 400 billion years ago is true today and will be 400 billion years from now.

Together, these characteristics make truth the smallest and largest thing in the world.

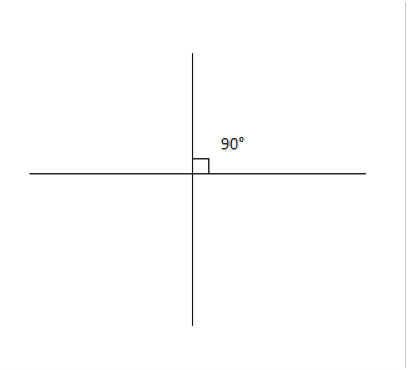

If we were to geometrically visualize truth, then, it would look something like two perpendicular lines:

Now, think back to geometry. A line, though represented as a mere inch or two on paper represents an infinite, two-dimensional line. It goes on forever.

When two lines intersect at a right angle, they form an infinite plane.

An infinite plane encompasses everything. Like truth, it is both narrow (two two-dimensional lines) that go on forever and ever, forming a plane that goes on forever.

The truth, then, is both infinitely narrow and infinitely broad. Like perpendicular lines.

Or this:

Expansive enough to encompass everything with no room for error.

Deo gratias!